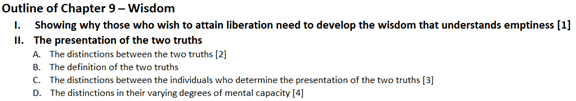

(9.3) Of those who assert the two truths, two types of person can be distinguished:

Madhyamika-Prasangika Yogis and proponents of things.

The views held by the proponents of things, who assert that things are truly existent,

Are refuted by the logical reasonings of the Prasangika Yogis.

There are many different philosophical schools of emptiness. The highest view of emptiness is the Madhyamika-Prasangika view. As a shorthand, usually we just refer to this as the Prasangika view. Shantideva is a Prasangika. From a Prasangika point of view, there are two types of being: proponents of things and Prasangikas. A proponent of things believes that objects do truly exist. There is something that is a car, a computer, and so forth that exists independent of the mind within the object.

A Prasangika, or a proponent of no thing, says that nothing truly exists. There is no object that exists from the side of the object. If we look, we cannot find something that is the computer, something that is the car, and so forth. A proponent of things believes that we can find something that is the object. A Prasangika says when we look with wisdom, we cannot find anything. Amongst the proponents of things, there are many different philosophical schools about where exactly we can find the object that truly exists. Some say the object exists in the material substance, some say it exists as the collection, some say it exists inside the mind, but that the mind itself truly exists, and so forth. All proponents of things believe that the object itself can be found upon investigation. The Prasangikas refute all of these views.

The table for example is a thing. According to Madhyamika-Prasangikas, there is no-thing that is the table. There is nothing that is the table. Madhyamika-Prasangikas are proponents of no thing. Unlike us, proponents of things believe that there exists something that is a table. There can be found something that is table. Different schools believe it is a different thing that is the table. The Prasangikas refute all of these views.

(9.4) Moreover, among the Prasangika Yogis, there are different levels of insight –

Those with greater understanding surpassing those with lesser understanding.

All establish their view through valid analytical reasons.

Giving and so forth are practised without investigation for the sake of achieving resultant Buddhahood.

The first line that there are different levels of insight amongst the Prasangikas does not mean that they are realizing a different emptiness. For a Prasangika, all emptinesses are the lack of inherent existence. The different levels of insight correspond with the different degrees to which the Prasangika realizes directly not all phenomena lack inherent existence.

Another way of understanding the different levels amongst Prasangikas is the motivation with which we realize emptiness. In general, we can say there are two levels of philosophical tenants: Hinayana and Mahayana. Normally when we talked about Hinayana and Mahayana we are talking about the motivation of the practitioner. A Hinayana practitioner seeks individual liberation, and a Mahayana practitioner seeks full enlightenment. The Hinayana schools of emptiness are the Vaibhashikas and the Sautrantikas. And the Mahayana schools of emptiness are the Chittamatrins and the Madhyamikas. We will get to know the tenets of these four schools of emptiness as we progress through Shantideva’s explanation. At this point, we can note that it is possible to hold Hinayana philosophical tenants yet possess a Mahayana spiritual motivation. Likewise, it is possible to be a holder of Mahayana philosophical tenets yet possess a Hinayana spiritual motivation.

We also need to be very clear on our motivation for meditating on emptiness. It is not enough to just gain an intellectual understanding of emptiness within our mind, we need to firmly establish that things are actually this way. When this is established within our mind, the more things appear different than the way we know they are the more it will confirm for us that things are empty. It is like when Neo went back into the Matrix after he found out what it really was – the Matrix still appeared vividly, but he knew it was just a simulation.

To emphasize this point I will read what Geshe-la says in Eight Steps to Happiness in the chapter on ultimate Bodhichitta. We can remind ourselves of this as we study Shantideva’s verses. Right at the very end of the chapter he says:

“When we study emptiness it is important we do so with the right motivation. There is little benefit in studying emptiness if we just approach it as an intellectual exercise. Emptiness is difficult enough to understand, but if we approach it with an incorrect motivation this will obscure the meaning even further. However, if we study with a good motivation, faith in Buddha’s teachings, and the understanding that a knowledge of emptiness can solve all our problems and enable us to help everyone else solve theirs, we shall receive Buddha’s wisdom blessings and understand emptiness with greater ease. Even if we cannot understand all the technical reasoning, we shall get a feeling for emptiness, and we shall be able to subdue our delusions and solve our daily problems through contemplation and meditation on emptiness. Gradually our wisdom will increase until it transforms into the wisdom of superior seeing and finally into a direct realization of emptiness.”

The last line of this verse refers to the apparent contradiction between realizing that everything is empty and engaging in virtuous actions towards other living beings. If the beings we normally see do not exist, then why bother engaging in virtuous actions towards them. Shantideva says we can overcome this objection by simply engaging in virtuous actions without investigating more closely the exact nature of the existence of living beings. The main point here is we do not practicing giving, moral discipline, etc., because there are really other beings there, but because by doing so it functions to create the result of enlightenment within our mind. For example, when we do taking and giving practice, we strongly believe that we have actually liberated all living beings from their suffering. We do this not because we actually have liberated all beings, but by believing we have we complete the karmic action we are after which will ripen later in the appearance of our dream filled with beings free from all suffering.