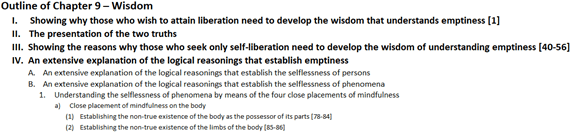

(9.85) Just as the body lacks true existence, so do its parts such as the hands;

For they too are merely imputed upon the collection of their parts, the fingers and so forth.

The fingers, in turn, are merely imputed upon the collection of their parts, such as the joints;

And, when the joints are separated into their parts, they too are found to lack true existence.

(9.86) The parts of the joints are merely imputed upon a collection of atoms,

And they, in turn, are merely imputed upon their directional parts.

Since the directional parts, too, can be further divided,

Atoms lack true existence and are empty, like space.

And when we look for the parts, we just find the parts of the parts, nothing more. We keep looking, and no matter where we look, we find nothing. We think we are surrounded by reality, but in truth it is all an illusion. There is nothing here at all, it just appears that there is. It’s a very nice meditation to do sometime, just go to the parts of the parts, and just end up finally meditating on space-like emptiness, realizing that even the atoms lack true existence.

Again, this does not require any faith to realize. This is something we can prove to ourselves with investigation. Emptiness is the definitive valid reason that establishes the rest of the path. If we can establish emptiness, we can prove every other stage of the path – death, lower realms, karma, renunciation, cherishing others, taking and giving, bodhichitta, tantra, everything.

When we think about it, it is truly amazing. Everything appears so vivid and appears so real, but when we actually look for it, we find nothing. It is all one giant illusion. It appears real, it has shape it has form it functions we can touch it, yet when we look for what is behind these appearances we find nothing. Our mind simply connects the dots and projects everything in between them. In fact when we look, we don’t even find the dots. Each dot itself is simply yet another hallucination, another illusion, another hologram.

Very often we can develop doubt, am I wasting my life practicing the spiritual path? I see everybody else off doing different things, enjoying life. But here I am, dedicating all of my time to trying to attain some state beyond this life. I am trying to construct a pure land and identify with myself as a deity. What if this is all a bunch of nonsense? What if none of it is true. What if it is all just a waste of time and I’m just engaging in make believe?

We can have these doubts. If we do not have an answer to these doubts, they can become crippling, and we lose all the motivation to engage in our spiritual path. We start to think that our spiritual guide and our sangha are perhaps deceiving us or themselves have been fooled into wasting their life chasing these fantasies.

How do we overcome this doubt? Through this meditation on emptiness. We identify the emptiness of our body, then we look at the emptiness of each of the parts of our body, then we look at the emptiness of the parts of the parts of our body, and so forth all the way down to atoms. We then look at the emptiness of atoms – made up of electrons, neutrons, and protons. Each of these things can be broken down further and further yet no matter how much we break it down, we continue to find absolutely nothing. There is nothing actually there. Our mind is simply projecting that there is something there, connecting dots that are not there, creating a mental illusion that our ignorance grasps at as real.

This is something we can prove to ourselves through investigation. There’s no doubt when we investigate, we find nothing. The self we normally see, the body we normally see, the world we normally see does not exist. It just appears to exist, like an illusion. It is all created by mind. We’re like those people who believe in conspiracy theories who see random data points and then fill in elaborate stories connecting those dots, grasping at their stories as somehow being true. We are exactly the same. Somebody trapped in samsara is in fact simply somebody who’s grasping at its conspiracy. But when we check, when we investigate, we realize it is all a big lie. Samsara is fake news. It is all created by mind.

If it is created by mind, then mind can create new worlds, different worlds. Here again we have direct experience. Before we viewed something as a hardship, later we came to view it as a blessing. What was it? Was it a blessing or was it a hardship? In reality it was nothing. From its own side it is absolutely nothing. But our mind can relate to it in different ways, and then we experience it in different ways. This shows that we can create with our mind the world that we inhabit and the world that we experience. Seeing this, we realize we can create any world, including the pure land. It just takes enough mental action to create enough karma to cause our abiding within the pure land to become a self-sustaining experience. Karma is proven by emptiness. Tantra is proven. Future lives are proven. Everything is established through emptiness. We could have 100% confidence in our spiritual path because of emptiness, which itself can be proven.