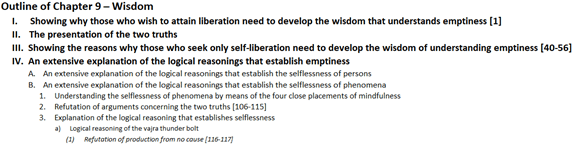

And now we come to the actual reasonings establishing selfless or emptiness. In total, Shantideva provides three main lines of reasoning establishing emptiness. The first of these reasonings being the reasoning of vajra fragments or the vajra thunderbolt (a much cooler name, to be sure). This reasoning establishes selflessness by refuting inherently existing production, or how are things created. The second is the logical reasoning of dependent relationship, which Je Tsongkhapa praises as the king of all reasons. The third is the emptiness of production of phenomena. You can find more detail on all of these in Ocean of Nectar and Meaningful to Behold. As with all of Shantideva’s instructions, what matters is how we can extract some practical value for our daily lives. We should not relate to this as merely an academic or philosophical exercise.

The refutation of the vajra thunderbolt establishes that all of the different ways in which production lacks inherent existence. Shantideva does so by refuting production from no cause, production from a permanent cause that is other, production from a permanent general principle, again production from no cause, and then production from both self and other. This exhausts all the different possibilities for how a phenomena can be produced. If each one of these is established to be empty, then all forms of production are empty. If all production is empty, then all effects of that production are likewise empty because it is impossible for an empty cause to create a truly existent effect. Thus, by establishing the emptiness of cause and effect, we attained the union of the teachings on conventional truth, or karma, and ultimate truth emptiness. In Je Tsongkhapa’s Three Principal Aspects of the Path he explains that the final view of emptiness is the one in which by affirming karma we establish emptiness, and by affirming emptiness we establish karma. This relationship is established through the vajra thunderbolt.

The first refutation is the refutation of production without a cause.

(9.116) Even worldly people can see clearly

That most things arise from causes.

The different types of coloured lotus, for example,

Arise from a variety of different causes.

(9.117a) (Charavaka) And what gave rise to that variety of causes?”

This question of the Charavakas is a very common question that modern people ask. How did it all begin? What started at all? The answer scientists give is The Big Bang. Other scientists then say, well what caused The Big Bang? Their answer is it arose from the collision of two different universes which then created our universe. But what then started those other universes? In our mind, there must be some point at which things began here. In the Bible, it says “in the beginning, …”

(9.117b) A previous variety of causes.

The prasangikas do not mess around. They simply say what caused the variety of causes? A previous variety of causes without beginning. Is very difficult for us to understand how something cannot have a beginning because everything we see appears to have a beginning , so we naturally assume the universe as well also has a beginning. There are a couple of analogies which can help us understand how something can exist , function, and change yet not have a beginning. The first is a circle. Where is the beginning of a circle? It has no beginning and it has no end. The second analogy is the ocean. Waves rise and waves fall but the ocean always remains. We can identify the beginning or end of a wave but not the underlying ocean. Now of course, we can identify the beginning of the ocean itself when water arrived on asteroids and hit this planet. But the point is making the distinction between the waves and the ocean. So we need to forget about the fact that the ocean did have the beginning. No analogy is perfect, so we take from the analogy what we need to be able to understand the point of Dharma.

If we think about it carefully, it is impossible to have a beginning. If there is a beginning, what caused the thing to begin? If there was a cause that existed before the beginning then there was something that was there before the beginning and thus the beginning is not the beginning. The only way to establish a beginning would be to say that the beginning itself had no cause. If there was a cause of the beginning, then the beginning would no longer be the beginning because cause must precede effect. This is why the first aspect of the vajra Thunderbolt is refutation of production from no cause.

(9.117cd) (Charavaka) “But how does a distinct cause give rise to a distinct effect?”

The Charavakas again ask a good question, namely how does a specific cause give rise to a specific effect? The modern equivalent of the Charavakas would be those who believe in chaos theory. Essentially things are so complex, it is impossible to establish cause and effect of anything, it’s as if everything is somewhat random. If people assert that there is anything that is random then that thing is necessarily something without a cause. Most people believe there is a good deal of random in the world. Some things have causes and some things are just random. Logically, all of the random things that happen are, for believers in random things, things produced with no cause.