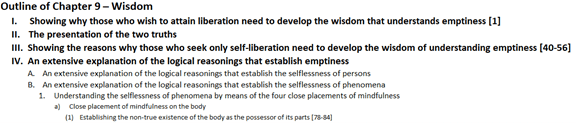

Shantideva now goes on to give reasons establishing the selflessness of phenomena. This is the largest section of Chapter 9. He essentially provides two main arguments establishing the selflessness of phenomena. The first is the four close placements of mindfulness. These look at the emptiness of the aggregates that form the basis of imputation for our I. The second method is to examine the relationship between emptiness and cause and effect. According to the Three Principal Aspects of the Path, Je Tsongkhapa says that when emptiness reaffirms karma and karma reaffirms emptiness, then our understanding of both emptiness and karma is correct. The outlines of Shantideva’s argument are quite detailed and it is easy to get lost in the details and forget what the main point is that he’s trying to establish. The goal is to establish the emptiness of phenomena. There are two ways that he does so: establishing the emptiness of our aggregates and establishing the emptiness of cause and effect. Everything else flows from this.

What follows is a classic meditation on the emptiness of our body. We are all familiar with this meditation since it shows up in all of our Dharma books. The fundamental point is we first need to identify the object of negation: the body that we normally see. The body that we normally see appears to exist from its own side, independent of our mind. It appears to be a singular entity we call my body. If such a body exists, it should be findable. There are three possibilities it is one of its parts, it is the collection of its parts, or it is somehow separate from its parts. There is no other possibility. If it cannot be found in one of these possibilities, then the body that we normally see does not exist. First, Shantideva looks to see if the body is one of its parts.

(9.78) Neither the feet nor the calves are the body,

Nor are the thighs or the loins.

Neither the front nor the back of the abdomen is the body,

Nor are the chest or the shoulders.

(9.79) Neither the sides nor the hands are the body,

Nor are the arms or the armpits.

None of the inner organs is the body,

Nor is the head or the neck.

So where is the body to be found?

None of the individual parts are the body itself, they are parts of the body. We make a distinction between the parts and the part possessor. The body itself is the part possessor, which is necessarily distinct from that which it possesses.

(9.80) If you say that the body is distributed

Among all its different parts,

Although we can say that the parts exist in the parts,

Where does a separate possessor of these parts abide?

When we look, we find only parts. There is no actual part possessor. None of the individual parts of the body is the body, and there is no thing separate or within the body that is the possessor of these parts. We simply have parts.

(9.81) And if you say that the entire body exists

Within each part, such as the hand,

It follows that there are as many bodies

As there are different parts!

I don’t know anybody who actually thinks that the entire body exists within one of its individual parts. Obviously that is absurd. But, when we do a conventional search, that is exactly what we do. Someone says, “point to your body,” and we then point to some part of our body and say, “it is here.” We don’t mean that it is within an individual part, we are referring to the whole thing, but in fact we are just pointing to a part of our body.

(9.82) If a truly existent body cannot be found either inside or outside the body,

How can there be a truly existent body among the parts such as the hands?

And since there is no body separate from its parts,

How can there be a truly existent body at all?

Recall above we established that there is no fourth possibility. Either the body is one of its parts, the collection of the parts, or separate from the parts. But when we look in each of these three places, we cannot find something that is “my body.” We only find parts, perhaps collected together, but there is no part possessor anywhere that is “my body.” Yet, that is precisely the sort of body we normally see, grasp at, and refer to when we speak of my body. When we look for such a body, we don’t find it anywhere. If we can’t find it, then it does not exist.

The danger is we have engaged in these sorts of contemplations perhaps hundreds of times, and they no longer move our mind. We just intellectually go through them, “yeah, yeah, not one of its parts, not the collection, not separate, check.” We need to instead, each time we meditate, go looking for the object just as we would go looking for our keys. We know they have to be somewhere. We have to be convinced we will find it so that when we don’t, we get the point – the body we normally grasp at and are convinced exists in fact does not exist at all. There are just parts here, nothing more.

(9.83) Therefore, there is no truly existent body,

But, because of ignorance, we perceive a body within the hands and so forth,

Just like a mind mistakenly apprehending a person

When observing the shape of a pile of stones at dusk.

(9.84) For as long as the causes of mistaking the stones for a person are present,

There will be a mistaken apprehension of the body of a person.

Likewise, for as long as the hands and so forth are grasped as truly existent,

There will be an apprehension of a truly existent body.

Normally we see a body within its parts. But when we check, we do not find one. The key question in identifying emptiness – what is the part possessor? We think there is one, but when we check, there is none. The analogy of a pile of stones at night is very good. From a distance, we see a body, one that appears vividly to our mind. But when we investigate closer, the appearance disappears and we see just a pile of stones. In the same way, we see a body, one appears vividly, but when we check, we find only parts. The appearance of a body is a mistaken apprehension.